Rolls-Royce in America

The Springfield Museums are featuring How People Make Things, a hands-on exhibit that explores manufacturing inspired by Mr. Rogers’ Factory Tours through May 9. The exhibit also features many Springfield Firsts, including the honor of being chosen as the first and only American manufacturing site for the Rolls-Royce. In this blog, John Robison explores the history of Rolls-Royce manufacturing in America.

The year 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of the American Rolls-Royce motorcar.

The first American-made Rolls-Royce was delivered February 29, 1921. Wallace Porter of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, drove S104CE away as a bare chassis, with just a grille, hood, and windshield, test seats, and a ballast box. By all accounts, he was thrilled with his new car. He’d followed its construction from the beginning, with an insider’s access. His father’s company had supplied the turret lathes Rolls-Royce used to machine the shafts and links on Wallace’s car, and he was very proud of that.

A car enthusiast of today might say, “That’s not a car at all!” Indeed, a chassis is not a finished car. It is the foundation. The addition of a body makes a complete motorcar. In England, companies like Rolls-Royce did not build complete cars. Instead, they delivered their chassis to coachbuilders. These coachbuilders were often descendants of firms who made horse-drawn carriages a generation before. Clients specified the style and amenities of their motorcar bodies, making each one unique. This was the opposite of Henry Ford’s standardized mass production, and exactly what some wealthy clients wanted.

A week after Wallace took his car, the Springfield plant completed another chassis. Then two more. As that happened, newspaper publicity brought in more orders. Momentum was building through the first half of 1921 . . . and then the company shut down. They had orders, and partly built chassis, but they had run out of money. The company had barely gotten started, and already they had financial problems.

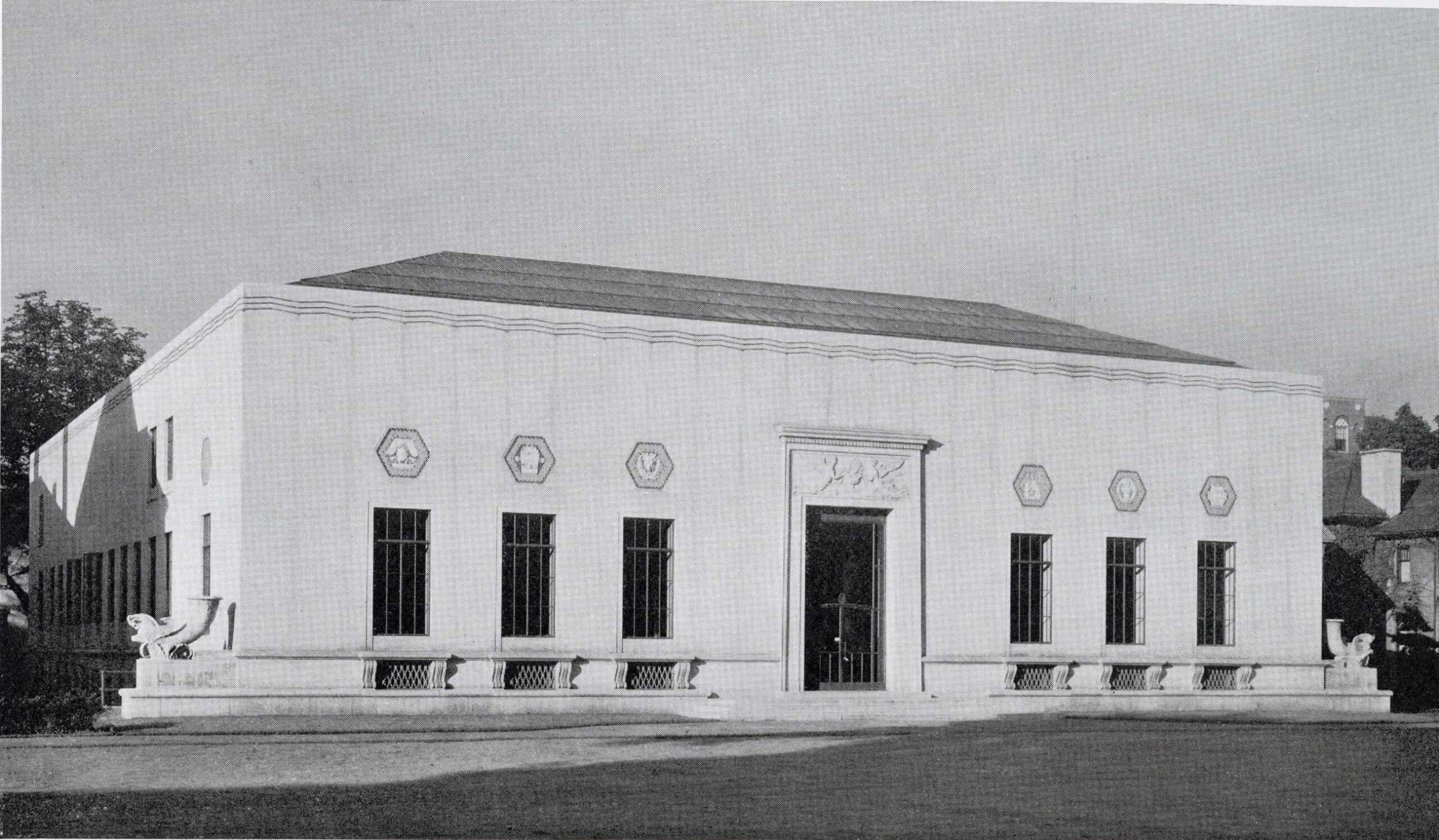

The company entered 1922 with a smaller workforce. Even so, they completed 230 chassis. Business was better for 1923, but a bigger problem reared its head. Some potential customers shied away from buying a Rolls-Royce because they wanted to purchase a complete car, not a chassis and a body. Management listened and found a space nearby where they assemble bodies and chassis. This space was the former home of the Knox car company and was now vacant.

Knox had been one of the first car makers, starting production in 1899. They grew quickly but other cars surpassed them in the market. Sales collapsed as fast as they had risen, and Knox ceased car production in 1914. Their plant was just two miles from the new Rolls-Royce factory, making it an ideal spot to paint and trim bodies that were made by various New England coachbuilders.

Over the seven years the American Rolls-Royce plant operated, car sales in America had more than doubled, but Rolls-Royce numbers barely grew. While Rolls-Royce had always been a luxury brand, some wealthy people just wanted practical transportation. Nothing epitomized that better than Ford’s 1928 Model A. With a basic model selling for $400 and nicely trimmed sedan just over $1,000, Ford sold almost a million cars that year. In a closer comparison, GM’s Cadillac division sold almost 50,000 cars that year.

The American Rolls-Royce management realized the auto industry was leaving them behind, and they worked out a plan for a smaller and less expensive Phantom. Chief engineer Olley brought the idea to headquarters in Derby, but the British management turned him down. They felt a less expensive car would destroy the brand’s exclusivity.

The car business had moved from cottage industry to big business incredibly quickly. In 1928, Ford was still a private company, owned by Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford, and their son Edsel. It had owner’s equity of $700 million dollars, and cash reserves of $370 million. That made the Fords one of the richest families in the world.

Rolls-Royce executives must have been sobered to read an April New York Times story, where Ford put the costs of starting Model A production at $25 million. At the same time, they projected volume would reach 6,000 cars a day within four months. After 8 years of work Rolls-Royce had not reached the level of production Ford attained in one day. Ford was getting more for their dollars via mass production and economy of scale, and the gap would only widen.

At its peak the Rolls-Royce plant was part of a thriving industrial community surrounded by worker homes. By 1939, in the depths of the depression, most of the plants were vacant and the homes were falling into disrepair. Rolls-Royce had spent $440,000 to buy the Springfield plant. The empty buildings brought Rolls-Royce bondholders just $65,000 when they sold that summer.

Two years later, the space was taken over by the US government, to become part of the Springfield Armory.

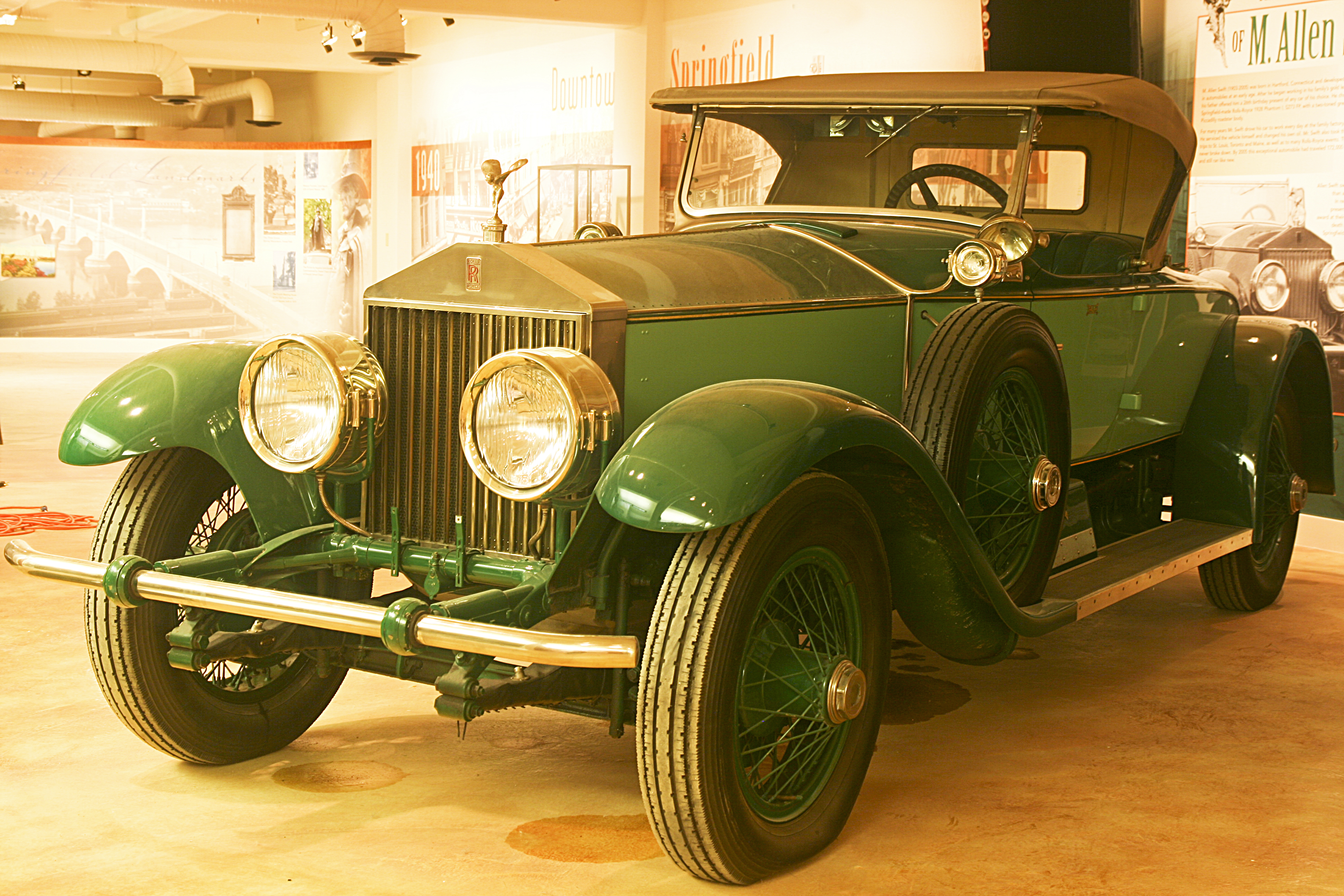

The East Springfield industrial area where Rolls-Royce was located is depicted in exhibits at the Lyman and Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History. The museum showcases motor vehicle production in Springfield, including cars and memorabilia from Duryea, Stevens-Duryea, Knox, Atlas, and Rolls-Royce. Featured is a 1928 Rolls-Royce Phantom, the gift of Allen Swift. Swift owned, drove, and cared for this Rolls-Royce his entire life. It now sits next to a 1925 Piccadilly Roadster owned by S Prestley Blake, co-founder of Friendly Ice Cream.

This blog is excerpted from Flying Lady magazine, from the Rolls-Royce Owner’s Club of America. The spring issue is devoted to the 100th anniversary of Roll-Royce in America. Members can see it online and in print.

John Robison writes at robisonservice.blogspot.com. J E Robison Service still maintains Rolls-Royce motorcars on a corner of the former industrial park that was home to Rolls-Royce of America, at 347 Page Boulevard.